Five Forums On Boston Desegregation

Forum I. September 26 at 6:00 at Roxbury Community College

The Segregation of the Boston Public Schools and the community organizing and legal efforts to try to eliminate segregation and to secure educational justice for Black students 1960-1973.

Covering the education issues brought by community groups to the Boston School Committee and their reaction, the Stay-Outs and Freedom Schools involving 8,000 students on two occasions, passage of the first Racial Imbalance Law in the country in 1965, starting Operation Exodus to transport Black students to vacant seats in better resourced white schools, starting METCO to give some students of color a chance to attend suburban schools, etc.

Forum II. June 2024 at the Federal Courthouse in Boston

The Legal Cases on Boston Desegregation: State Supreme Court Cases and the Federal Court Decision finding that Boston’s Schools were unconstitutionally segregated in Tallulah Morgan vs. James Hennigan, June 1974, and Ordering the Remedy of Busing

State efforts by the State Department of Education and the State Supreme Court to enforce the Racial Imbalance Law, resistance by the Boston School Committee. The filing in 1972 of Tallulah Morgan vs. James Hennigan with 14 adults and 43 children as plaintiffs. The Trial. The decision by Judge Garrity in June 1974 finding that the Boston School Committee had "intentionally brought about and maintained racial segregation" in the Boston public schools.

The impact of the July 1974 decision of the Supreme Court in Milliken vs. Bradley against desegregation across city lines. The Phase I busing plan of September 1974 and the more extensive Phase II busing plan for September 1975.

Forum III: Fall 2024

A Town Meeting on what happened and the legacy of busing and desegregation. Held at the Boston Public Library in Copley Square

Part 1: 10am-12pm Part 2: 12:30pm-2:30pm

Part 1: What happened in Boston’s schools and neighborhoods with the momentous events of desegregation and busing 1974-1976.

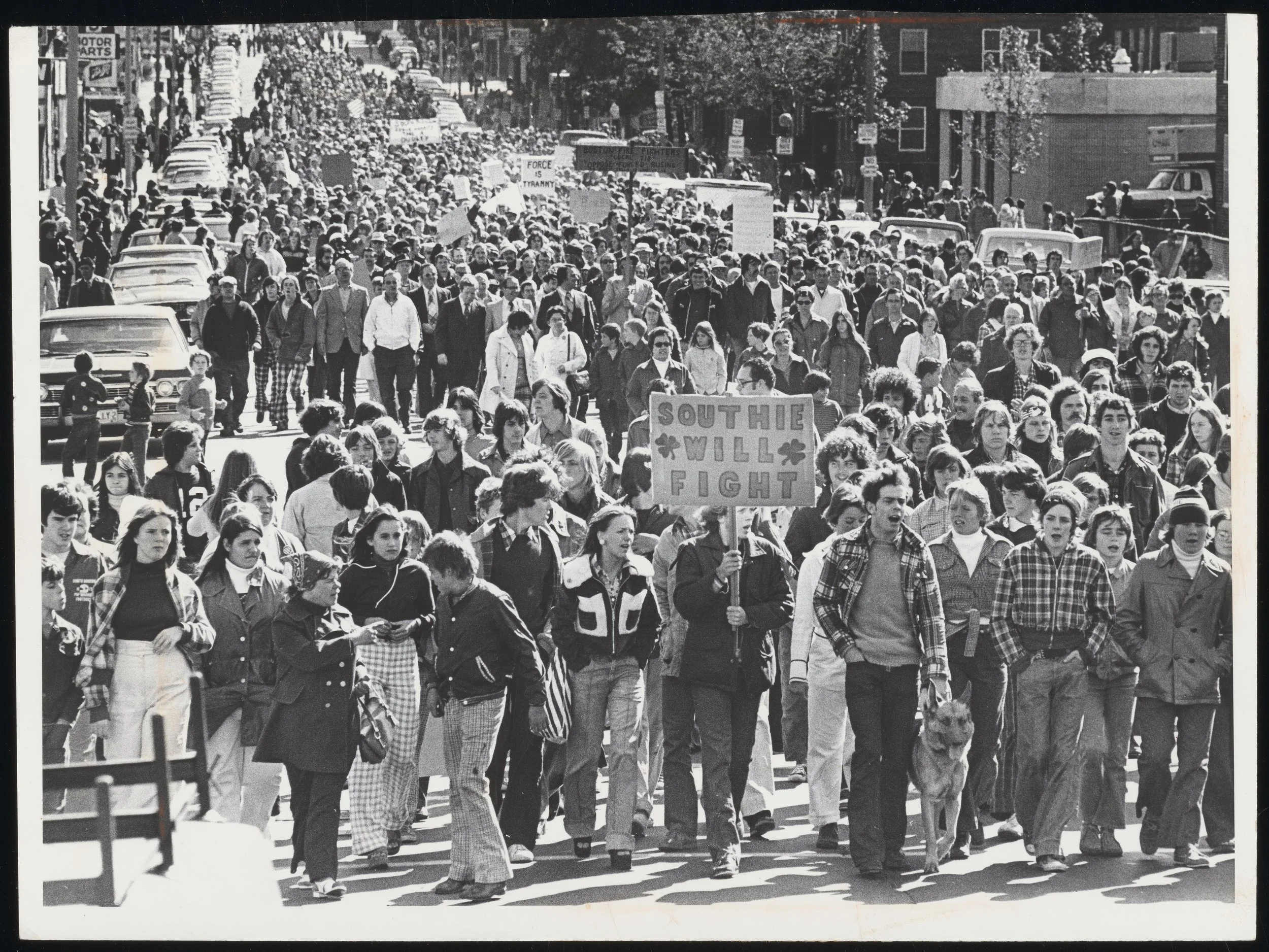

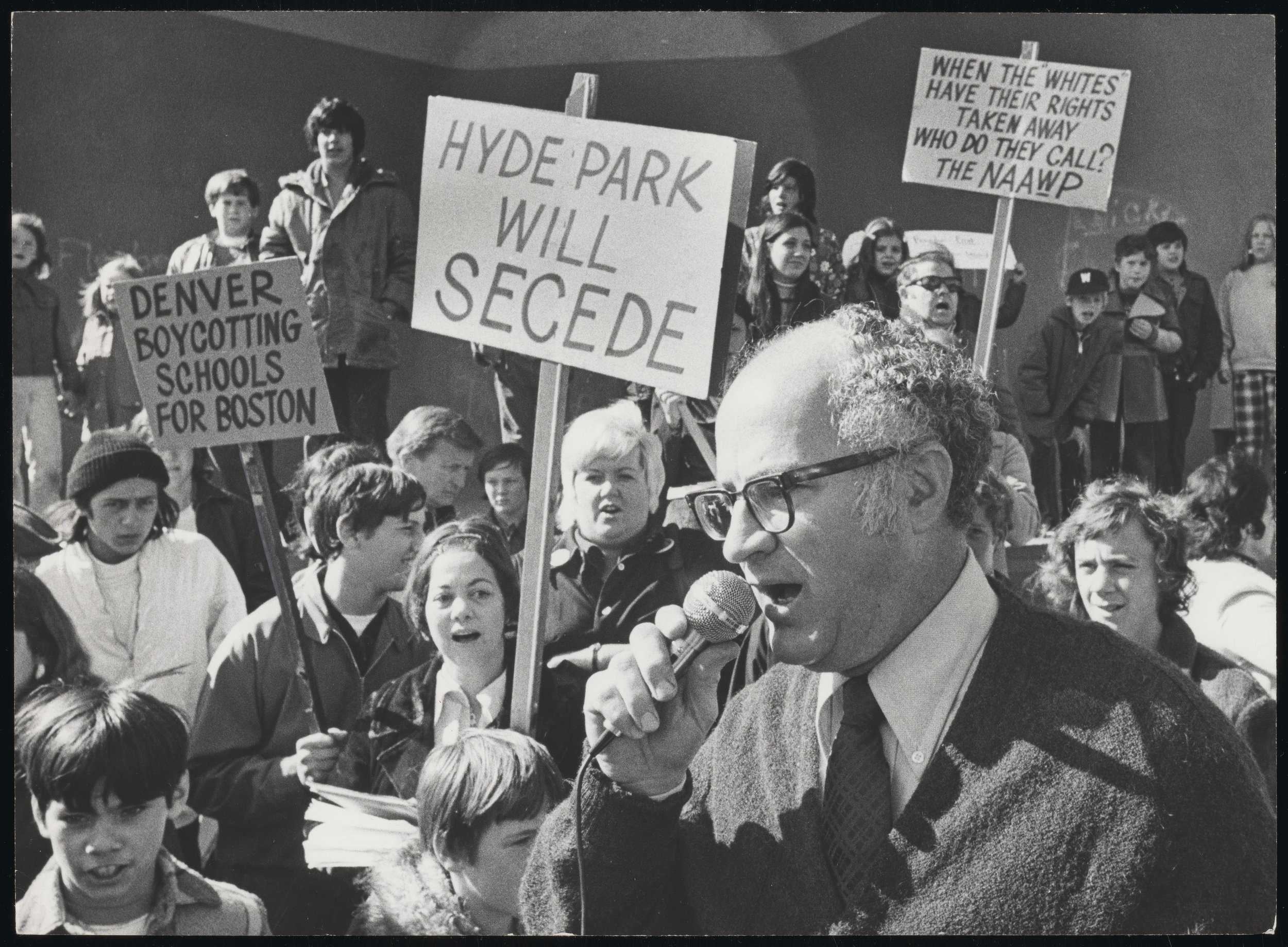

When desegregation was implemented by busing in the fall of 1974, there was large scale organized resistance from working class and poor whites and even violence by some white residents in South Boston, East Boston, Hyde Park, and parts of Dorchester. Some elected officials, including the Chair of the School Committee, Louise Day Hicks, provided political support to the opponents. Racial conflicts including violence at South Boston High School, Charlestown High School, and Hyde Park High School were traumatic for Black students bused to those schools and for some White students. There were also racial tensions in other high schools and middle schools, but many schools proceeded peacefully. There were also numerous legal appeals by the School Committee, all of which were rejected by the Federal Courts.

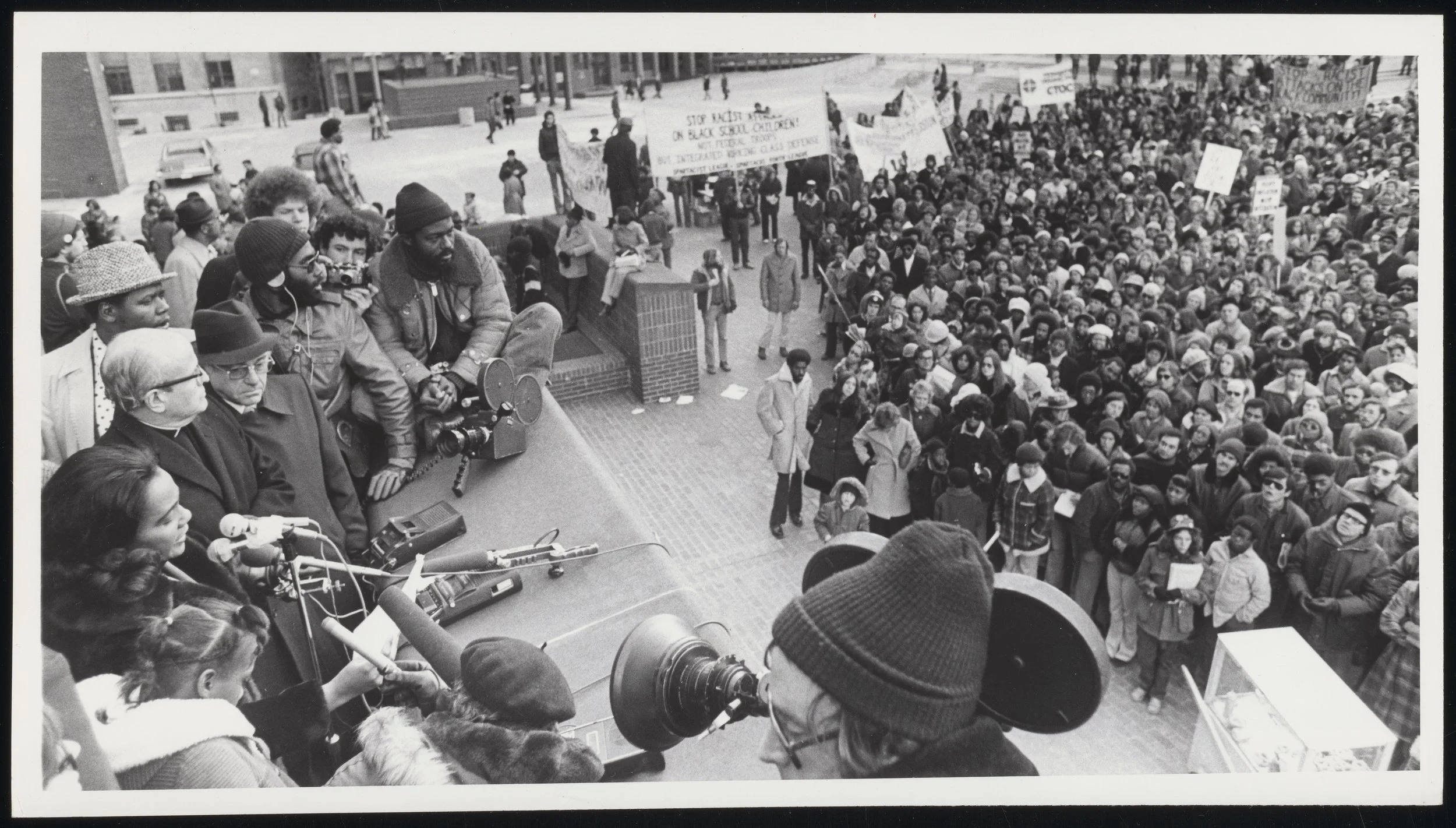

At the same time, strong organized support came from civil rights leaders and organizations, legal advocates, including the NAACP, Freedom House, some Black officials, and many parents, students and residents across the City who had fought for desegregation of the schools. The Citywide Education Coalition (CWEC) and the school based, district based, and citywide parent councils established by the Federal Court and the United States Justice Department’s Office of Community Relations all worked to ensure peaceful transitions at newly integrated schools, as well as in the neighborhoods opposed to desegregation.

Part 2: The Legacy of Desegregation and Busing -- Success or Failure?

Between 1974 and 1980 the Boston Public Schools underwent profound changes in student demographics, teacher and administrative integration, more equitable funding of schools, new curriculums, partnerships with universities, and corporations, health centers and other organizations, and a requirement that 1/3 of students in the Exam Schools be students of color (this last one was overturned in a case in the 1990’s brought by a white parent and then aspects restored last year). Also central to these changes were the establishment by court order of racial-ethnic parent councils at local schools, school districts and citywide. These councils brought together hundreds of parents in support of school desegregation and to advocate for more active participation in areas such as selecting school principals, reviewing school budgets, and ensuring the safety of all students. Lastly, the defeat of those School Committee or City Council members in the 1977 elections who opposed desegregation, including Louise Day Hicks, began a long period of change in Boston’s political landscape.

Yet despite these changes, Boston’s schools continued, like many other urban school systems during this period and up to the present, to struggle with enormous challenges to provide quality education to all its students. These challenges include: white flight to the suburbs and white students transferring to some parochial and private schools; the ongoing achievement gap affecting especially Black and Brown students; the failure to address the needs of special education students; the physical conditions in many school buildings; and problematic dropout and low college graduation rates of BPS students. And parents of many students of color enrolling their children in METCO and in charter schools.

Forum IV. Beyond Boston: Why the Suburbs were not included in the Boston School Desegregation Implementation Plan, How the Suburbs are still segregated, the Role of METCO in desegregation in 33 suburbs

A June 1974 Supreme Court decision made it hard to apply desegregation to communities outside of the major city where schools were segregated. Suburban policies by local government, by realtors, and by banks led to a lack of racial diversity in the suburbs. METCO was started by Black community leaders in the 1960’s as an additional strategy to enable better education for Black children. It’s grown to having 3300 students of color attend schools in 33 suburban communities.

We will examine how all these developments took place and next steps.